What makes a good Age of Vikings narrative? Here are some tips and ideas on how to make your Age of Vikings narrative even more compelling and fun.

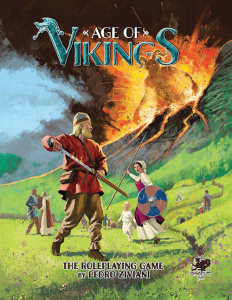

A good Age of Vikings narrative is born from the same raw material that shaped the sagas themselves. It grows from memory and landscape, from old feuds and whispered stories, from honor defended and insults remembered. Every role-playing game carries within it a sense of the story it wants to tell. Dungeons and Dragons leans naturally into dungeon crawls and monsters, Call of Cthulhu binds itself to cosmic dread, and Age of Vikings, by Pedro Ziviani, follows the pulse of the sagas. It carries a tone shaped by Iceland in the year 977, when the Norse world stretched wide across northern Europe and the Alþing had already stood for forty years. The great figures of the sagas walked the earth and the rule of the goðar was well established.

When you approach this setting, you stand before a question. What lies at the heart of its narrative. What kind of story does the game itself whisper to you. The answer sits in the pages of the rulebook, but also in the sagas, in the folklore, and in the sensibilities of the people who shaped these stories a thousand years ago. That is where you begin.

Starting Points

Almost all sagas open with quiet steps. They speak first of the deeds of ancestors, the victories and failings of forefathers, the wordless grudges held between families. Some readers drift past these early chapters, but they hold the scent of what is to come. They hint at conflicts waiting to unfold and reveal how long shadows can stretch across generations.

Characters in Age of Vikings carry the same weight. They grow up hearing stories of raids, journeys, quarrels, alliances, and the small slights that shaped their family lines. Even the most peaceful farms have their secrets. Perhaps a grandfather fought at Wineheath and returned with both fame and a deep hatred of the Scots. Perhaps a parent fell out with the local goði and refused to stand at the founding of Alþing. These pieces matter.

When you shape a saga with your players, work through these roots together. A character whose ancestor killed Þórólfur Skallagrímsson may suddenly find every meeting with a Skalla-Grímsson ally tense and fraught. A character who carries Hate (Scots) may discover that the campaign’s main antagonist is a Scot and feel the entire narrative sharpen around them. Family history is not flavor. It is the soil from which your story grows.

Conflict in the Sagas

Reading the sagas reveals quickly that conflict does not always rise from grand causes. People are rarely driven by ideology but by honor, pride, and the quiet burn of insult. A joke told at the wrong moment or a gift refused without grace can ignite a feud that spans years. Honor is therefore not a theme in Age of Vikings. It is a force. It defines worth more than treasure or cattle and it belongs to both men and women. A young woman protects the honor of her family until marriage, when she shifts to guarding that of her husband, but the principle remains unchanged.

Three great vices run like threads through the sagas. Murder without acknowledgment, breaking of oaths, and adultery. A murderer who flees responsibility, an oath-breaker who betrays trust, or a seducer who destroys a marriage all face harsh judgment from society. These vices even echo through Völuspá, where they are named among the corruptions of mankind. When you want your Age of Vikings story to feel true to its roots, let these vices and the defense of honor guide your narrative. They move the story forward effortlessly because they strike at what mattered most.

The Center and The Frontier

Nearly every saga shapes its world with two spheres. The center is the known world, most often Iceland, where daily life unfolds, where the Alþing gathers, and where farms and families anchor the characters. Beyond this lies the frontier, a place of uncertainty and myth. The farther the characters travel, the more legendary the narrative becomes. Gunnar’s exploits in the East or Búi’s encounter with the hidden king Dofri in Norway both take place far from the calm heart of Iceland. Even within Iceland a frontier exists, especially where the hidden people are said to dwell.

Age of Vikings embraces this beautifully. Characters begin in Iceland, surrounded by familiar customs and landscapes, yet the frontier lurks close. The hidden people, Álfheimur, and the spirits of waterfalls and mountains bleed into the edges of the mundane. Then the world widens. Journeys to Norway, Greenland, or the Hebrides expose characters to jarls, kings, raids, strange creatures, and unfamiliar customs. This contrast between the center and the frontier reflects the medieval T-worldview, where Jerusalem stood at the world’s heart. The sagas often tried to show that Iceland, despite its remoteness, belonged close to that center. You can use this same principle when shaping your story.

The Magic

Magic in the sagas is quiet and deliberate. It does not roar across the sky. It slips through runes, whispered charms, curses, visions, and deceptive craft. Age of Vikings divides this into runes and seiðr. The runes carry the echoes of Hávamál, where Odin learns their secret powers. They are respected rather than feared and have practical effects, as when Egill Skallagrímsson used ale-runes to uncover a poisoning attempt.

Seiðr is more perilous. It is tied closely to women in most sagas, who wielded it with the same intent as a warrior wields a blade. They foretold futures, enchanted weapons, and bent the will of others. Men who practiced seiðr existed, yet were viewed with suspicion. When using magic in your narrative, remember that it should feel subtle and unsettling rather than spectacular. Its strength lies in its influence, not its spectacle.

Alþing

The þing is the heartbeat of the sagas. Conflicts reach their turning points there, not only through combat but through law, argument, alliances, and political maneuvering. Blood feuds are halted, marriages arranged, weregeld negotiated, and grudges rekindled. Leaving the þing out of your narrative is to strip away one of the strongest narrative anchors of the age.

The Age of Vikings sourcebook outlines Alþing well, but do not forget the smaller local þings. They offer conflict, drama, and opportunity equal to the national assembly. They allow characters to fight their battles on familiar ground where the social consequences feel personal.

The Hidden People and Mythical Creatures

Folklore tells of trolls, giants, hidden people, land-spirits, and all manner of creatures that walked Iceland before and after settlement. The people of the Viking Age believed in their presence and made offerings to them. Every hill and waterfall could hold a spirit or a guardian. By weaving these beliefs into your story, even as rumors or distant warnings, you allow the frontier to breathe. Encounters with the unseen become not surprises but natural extensions of the world.

The Age of Viking Narrative

After exploring the sourcebook, the sagas, and Icelandic folklore, you discover that an Age of Vikings narrative is built from ancestry, honor, conflict, center and frontier, subtle magic, political assemblies, and the unseen world that lingers just past the lamp-light. How you mix these elements is yours to decide. Blend them with your players’ histories and ambitions, and the saga you create becomes something living, shaped as much by your table as by the old stories themselves.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks